In one of the first Method Writing classes this session, I mentioned in passing a communist political group in the 30s known as the Lovestonites, after their leader Jay Lovestone, and a piece of art that appeared in the New Yorker a few years ago. But I didn’t really go into any detail. It was a throwaway reference having nothing to do with whatever we were discussing in class. But, who was this Jay Lovestone character, and why was he following me? And where was he now? In the 20s, he had been the director of the Soviet-backed Communist Party of America. In 1929, he was either expelled from the party or split off of his own volition (depending on whose account you read). In 1966, when I was in graduate school as a history major, I wrote my MA thesis on Jay Lovestone and his splinter group, who had broken with the Soviet party line. It was hard finding source material for him. His splinter party became known as “The Lovestonites.” There were actually two communist parties in America at that time:The Communist Party of America was affiliated with and followed the party line of the Soviet Union. They were known as the CPA, formed during the early 20s after World War I and the Russian Revolution. The other party was named the American Communist Party (or the ACP), totally home-grown. Many political parties were created after the Civil War, some of them indigenous groups that rose from the many populist movements, like the one that grew out of Robert LaFollete’s populist mid-western semi-socialist platforms. The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America (SDPA) and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of American (SLPA), which had split from the main organization in 1899. Like hapless Mickey in Disney’s Sorcerer’s Apprectice, political parties often splintered into other political parties, making it difficult to remember what splintered ideology each one represented. These groups usually drew significant support from trade unionists, progressive social reformers and immigrants. Eugene Debs twice won nearly a million votes in the presidential elections of 1912 and 1920. So the American Communist Party had no connection with Russia at all and espoused typically American leftist ideas. In 1929, many of those in the Communist Party of America broke with the official Soviet organization and formed their own splinter groups, such as the Trotskyites, the Cannonites, the Fosterites, the Lovestonites, to name only a very few. For instance, James Patrick Cannon was an American Trotsyist (or Trotskyite) and a leader of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). He was the son of Irish immigrants with strong socialist convictions, who organized throughout the Midwest. Following his expulsion from the CPA in 1928, he formed his own party called the Socialist Workers Party, known as the Cannonites. In 1953 he retired, moved to California and died in Los Angeles in 1974. I did my MA thesis in college on the Lovestonites, and when I wrote to Cannon with questions about Lovestone, he was kind enough to write me back. Jay Lovestone had been the leader of the CPA before splitting with Russia and forming his own splinter group, known as the Lovestonites. I was able to track down a few of these characters. One of them, ironically, was the father of Evelyn Klein, a girl I dated in high school. I wrote a poem about her, which you can find in my book LAST OF THE OUTSIDERS, on page 341, titled “Requiem.” or if you don’t have that book, you can find it in a previous collectio of mine, The Naked Eye: New and Selected Poems, on page 375. Anyway, I spent a few hours interviewing him, and got a few letters back from a few of those old radicals, but no one seemed to know where Lovestone was. It was as if he had vanished from the face of the earth, almost like he never existed. What happened to him, I wanted to know, so I could complete my thesis. Here’s what I eventually found out. He had morphed after World War II into a rabid anti-Communist and was a foreign policy advisor to the leadership of the AFL-CIO and various unions within it. The last I had heard at the time I was writing my thesis was that he worked as a “cloak-and-dagger” man for the CIA. It wasn’t unusual for many of those old commies to end up espousing conservative, right-wing causes. Will Herberg was Jay Lovestone’s second lieutenant in the party and edited the Lovestonite newspaper. Years later, Herberg wrote a book published in the late 50s which became a rather significant work of socio-political cultural criticism titled PROTESTANT, CATHOLIC, JEW. Herberg later became the editor of William Buckley’s conservative magazine The National Review. This is what is meant by the term “strange bedfellows.” Did Buckley realize Herberg had been a communist?

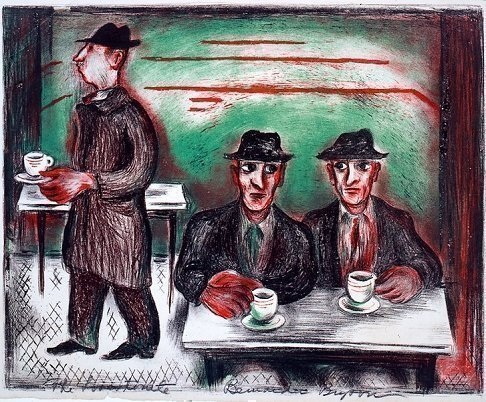

Anyway, I had come across a painting in The New Yorker a few years ago in an article on “Art and Revolution” and was surprised to find a piece by Bernarda Shahn titled “The Lovestonites.” Two guys sitting with a cup of coffee at a table in a New York “automat” and a third guy walking past them, also holding a cup of coffee.

Bernarda Bryson Shahn’s “The Lovestonite” from “Art and Revolution” in the

Jan. 26, 2015 issue of the The New Yorker about the exhibition “The Left Front:

Radical Art in the ‘Red Decade,’ 1929-1940.”

Were the two guys at the table “the Lovestonites?” Maybe all three were “The Lovestonites.” The third guy walking past the two guys at the table was obviously not going to sit with them. What was the point of this painting? Who were the Lovestonites? I doubted anyone would know who the Lovestonites were. But I knew. So here’s the subtext of that painting that was not contained in the New Yorker article. It was a running joke regarding those splinter groups that whoever owned the mimeo machine controlled the party, and many of those groups (there were dozens and dozens of them) often dwindled down to three members, and when they split, it was usually two guys against the one guy who had the mimeo machine. They often held their meetings in those “automats” that you could find all over Manhattan, popular in the 30s and well into the 50s. Imagine a wall stacked floor to ceiling with what could be called vending machines: sandwiches, fruit, veggies, whatever, stuff you could get for a dime or a quarter. Instead of something falling into a bin at the bottom, you just put in your money and you’d open the little glass door and retrieve the item. Whole walls stacked with these glass cubicles. My father often told me how in the 30s, when he was living on the streets and hadn’t a penny in his pocket, he’d go into the automat, get hot water (which was free), add ketchup (which was free), and any other sauces or condiments lined up on a table (all free), and he’d it all to a bowl of hot water, and voila! soup. For dessert, he’d grab a couple of sugar cubes next to the coffee machine. My father told us stories of his life on the streets in the 30s and how he bummed around America on freight cars and slept in YMCA’s and “hobo-jungles” across depression-era America. The story I remember most was how he rode into the Philadelphia stock yards in the depth of winter and got drenched by the water tank, knocking him to the ground. A burly railroad dick on the lookout for bums grabbed him up and was about to beat him to a pulp with his nightstick. Then he stopped, saw my father’s young, baby face (Dad was probably in his early 20s at the time), and said, “Jesus, kid, you’re gonna freeze your ass off.” He reached into his pocket, gave my father a quarter, and told him where to go to get a cup of coffee and a meal. “Sally’s Diner on the other side of the tracks,” he said, “can’t miss it. Tell her Big Bill Haywood sent ya!” These stories my father told us rose to the level of myth for me. And what was the point of every story. How in the depth of the depression, whatever the class or political persuasion, somewhere in people’s hearts was a leaning toward compassion for their fellow man. I thought my father was spinning magical tales, a Homeric poet recounting battles of an American Trojan War. But no, he was trying to remind me that we have to care for each other, that we have to see beyond class, race, social position or sexual orientation and treat each other with kindness and love. During the day, like many of his fellow homeless drifters who had nowhere to go, he slept in libraries. Most covered their faces with newspapers so no one would notice they were sleeping. But my father read books. His storehouse of knowledge from all his readings never ceased to amaze me. I guess you could call him a Marxist, one of those “fellow-travelers” who sympathized with the aims of the party though they never became members of it. His political ideals were very leftist and humanitarian. I remember he often quoted Marx, even correcting a translation I was reading that had gotten one of Marx’s famous metaphors wrong. My father was the most brilliant, generous, well-read, compassionate. funniest man I ever knew. And the best writer. He combined a magical lyrical gift for words with the street-smart roughness of a boy who grew up on the lower East side of New York and hung out with guys who later were executed as part of a group from Murder, Incorporated. Scorcese made movies about them. Yeah, those guys. I remember when their pictures appeared in the newspaper the day those so-called members of Murder, Incorporated, were executed. “I knew these guys,” he said over his coffee in the kitchen. He had hobnobbed with hobos and homeless drifters, and there wasn’t a book — it seemed — that he hadn’t read. He became an optician and opened his own place on Tulane Avenue in downtown New Orleans called Nu-Deal Optical. Met my mom, whose brother owned an optical place just a few blocks down the street. When I was a teenager, I worked in the store during the summers. I’d get there at 7am and clean out the “surfacing machines” that ground the lens to the exact prescription. All that glass ground into a trough of water, and you literally had to reach in, grab a handful of this beautiful white mud and dispose of it. I then worked the front of the store, behind the counter, waiting on all the country folk who came in with their families to get eyeglasses for one price, $4.95, which was affordable for those who could barely afford spectacles, paid with coins from a coin-purse tucked in their back pockets. I watched the way my father treated each person and marveled at his ability to connect with young and old, rich or poor. One time, a family had taken the bus from Homa, a small town across the lake, and they were waiting for their glasses and the lenses kept breaking on the “surfacing” machines in the back and my father could see they were getting impatient, needing to get to the bus-station to go back home. He finally approached the father and said, “Mr. Delacroix, if you stay here any longer I’m going to have to charge you extra for sitting in that chair.” The old Cajun burst out laughing. Ten minutes later, the whole family got their glasses in time to catch the bus back home. I remember asking him what he’d pay me if I worked in the store during the summer, and with that half-joking smile, he said, “Son, whatever it is I’ll pay you to work in the store, I’ll pay you twice as much if you don’t work there at all.” So that painting by Shahn brought together my father, the automats, my master’s thesis, and the joke about those leftist parties dwindling down to three people, two without the mimeo machine, and the one with it. If you had the mimeo, the saying went, you controlled the party. After mentioning the picture in the New Yorker, Lisa Segal, our resident research librarian, found the graphic in The New Yorker and sent it to me. So I’m passing along the painting and the story behind it. Like I said, few readers would know who Lovestone was, and even fewer would get the implicit joke in the subtext of the painting. The smug character walking past the two men seated at the table probably was the one with the mimeo machine, thus controlling the party. Look closely, he’s probably whistling. The expression on the faces of the two guys seated at the table is priceless, as if they had just realized that someone had picked their pockets. Anyway, now you know. All thanks to Lisa Segal, who can find any artistic needle in any literary haystack.

Addendum:

Lisa Segal just sent me this needle, making me wish I could go back in time and add this postscript to my college thesis:

Jay Lovestone died on March 7, 1990, at the age of 92. His massive accumulation of papers, encompassing more than 865 archival boxes, were acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives at Standford University in 1975. For 20 years, they remained sealed. In 1995, the material was opened to the public and was the source for Ted Morgan’s first full-length biography published is 1999. An associate, Louise Page Morris, later supplemented the collection with her correspondence. According to other reports, she spent 25 years as Lovestone’s lover. Lovestone’s FBI file is reported to be 5,700 pages long.