Description

First Edition*

Aphrodesia Press, 1967,

76 pages, 35 poems, illustrations by author, frontispiece by Allan Yasnyi, Introduction by Douglas Blazek, printed on linweave deckle-edge paper, wrap cover, 300 copies, out of print/rare $250

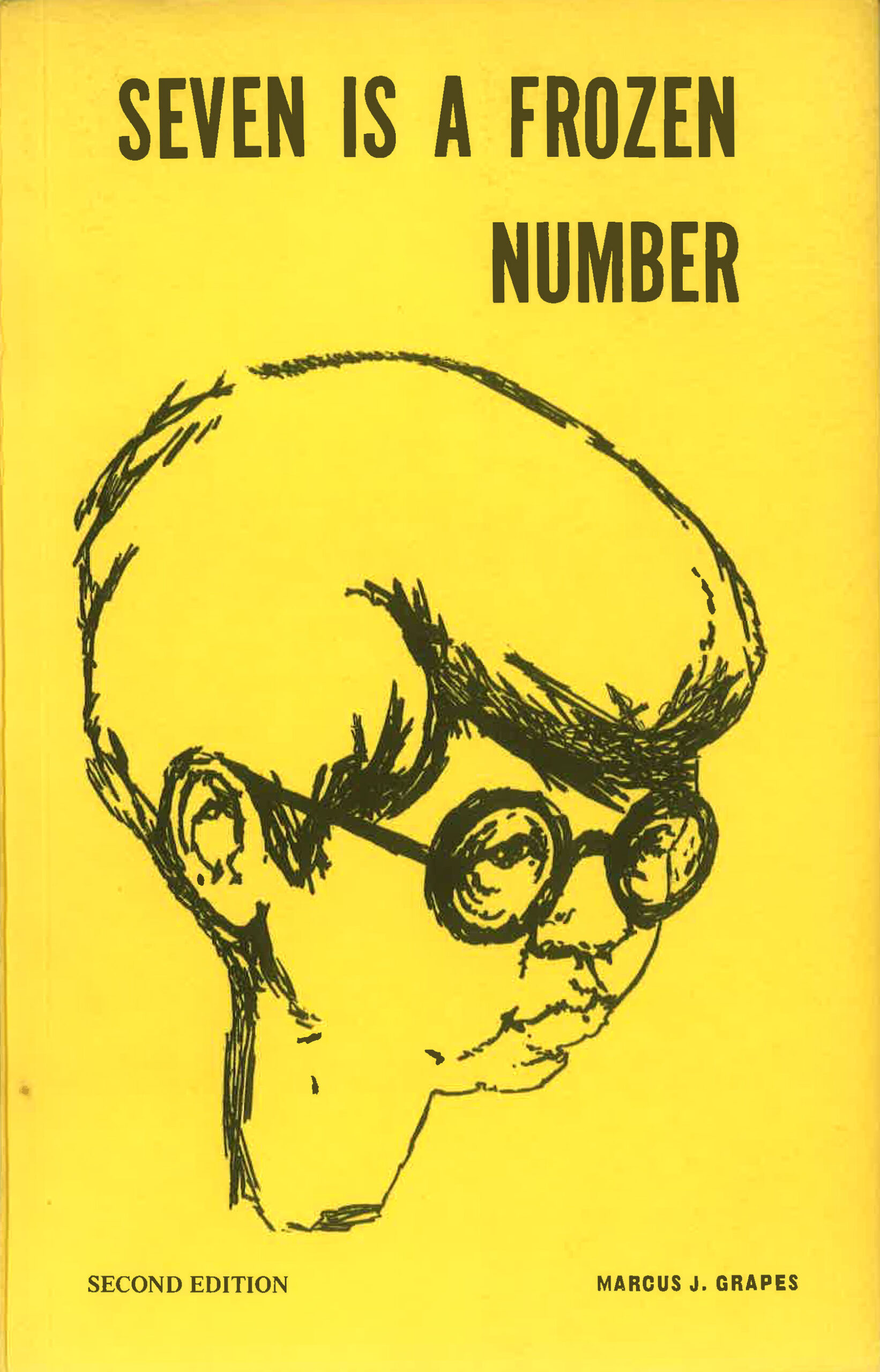

Second Edition*

1968, 500 copies, $200

*Check with author for availability

Reviews

Marcus J. Grapes has never read a poem in his life. He was born in a sunset & fell to earth like a smoothly flaming red yoke but as he fell nobody saw him and all through his twnety-some-odd years nobody has seen him except himself. It is this that he knows best: himself & the world he has fallen into, but he has not been spoiled by it, suckered in by any of its con-games; yet, by some quirk of fate, he has suffered as any human being has. All these things become ingredients in his poetry & whether this sounds like too much mystical bullcrap or not this is about the best way to describe Grapes’s writing that I have yet to find. When he writes about song it is song as a bird would know song. When he writes of loneliness it is loneliness as a man unseen by anybody would know loneliness. And when he writes about sunsets it is a sunset as only a man born in one would know them. There is a supreme & eloquent strength in Grapes’s standing alone — it keeps him out of the various ‘schools of poetry’ & his not having ever read a poem keeps him from doing anything but communicate what he knows. Grapes is not a poet, because that word implies crafting. He does not chisel or carge anything nor does he manufacture anything. He is a human being who was born more of life than any of us. As I said, he does not manufacture anything — he gives you a slight re-shuffling of life. In his poem “Summer Dies with Fat Laughter” he writes:

When my father died

an ocean was between us

and we were both

in the wrong place;

I made it back for the funeral

palmed to fortune’s fatness;

everything belonged in another place;

the sun kept with it

like a fist

and we made it to the cemetery

with our punched-in faces

standing around the grave.

This poem re-shuffles life so sensibly, so eloquently, but Grapes is so purely himself & so purely human; he has a tender caring passion that is hot & soft & is so frightfully real & so frightfully brings out dead selfish carcasses to feel more convincingly than ever before the full spectrum of the earth we live on. His poems are answers to problems our teacher gives us in school & we just can’t for the hell of it grasp what has to be done in order to solve it. In truth, Grapes doesn’t know anything and admits this, unlike those of us who parade around with knowledge of everything; but by not knowing anything he leaves himself open to receiving everything life offers as if life is supposed to be the way it is. As if living is an natural as his being born & ‘this which we call dying is only ceasing to die” — that life, birth, & death are one, & if there weems to be more pain than pleasure it is because human beings were not made for living — it is too much for them — they would be better off as fireplaces or dreams or snowflakes & when he writes

a bearded artist

cleaning his brushes

turns to look at the sky

and I wonder to myself

who will pain

the last sunset

it is easy for me to answer that Marcus will since he was first born of it.

Douglas Blazek, “Marcus J. Grapes: Obscure Flame,” Kaleidoscope, Vol I, No. 10, 1967

I dislike describing someone as a ‘promising young poet;’ it implies a lack of present value that I do not intend. But for want of a more comprehensive index of my reaction to Marcus J. Grapes’ Seven is a Frozen Number, I beg it’s excuse. In his introduction to this impressively crafted and handsome publication, Doug Blazek declares, ‘This book is one of the causes (of what) is happening in poetry. It’s being ripped WIDE OPEN! The whole scene is splitting like an overheated hot dog!’ And while Doug may be right about the scene, though I doubt it, I definitely cannot agree with his reason for claiming this good book is a good book. Perhaps it is as simple as his confusion between cause and effect. The ‘splitting from too much internal heat,’ the violence, is just not characteristic of this book. These sincere poems are soft-spoken and reticent. I see the poet who wrote them as giving a sad and undulgent smile in response to that which fragments his life. From a certain depth within himself, he expresses a compassion that, in the hands of a lesser poet than Grapes, would certainly deteriorate to a mauldin melancholia. He is not ‘boiling over;’ not a warrior. But Grapes is a poet. he creates his ‘reminiscence’ poems with a clarity that is frequently surprising and pleasing, and he is as

equally competent in controlling a phrase as he is in making the entire poem do what he thinks it should.

Jerry Burns, Small Press Review, Vol No. 2, 1967